The art of shooting movies is deeply rooted in technology. Artistic direction, lighting and story, no matter how profound and original, must all be captured with a camera and then projected before an audience can appreciate it.

Since the first images were captured, cinematographers have sought to manipulate, personalize and push the boundaries of film. But technology sometimes pushes into new frontiers, and art can be slow to follow.

Hollywood’s newest bold step forward is into high-frame rate films, or HFR, which dramatically changes how movies look. HFR refers to frame rates beyond the industry standard of 24 frames, such as 48 frames per second or 60 frames per second.

This technology, while not new, made a tremendous splash in the industry when Peter Jackson decided to film and screen his adaptation of The Hobbit at 48 fps. A number of film buffs and critics were dismayed at how Middle Earth appeared on screen.

New York Magazine film critic David Edelstein, for example, complained the “fakeness of the sets and makeup [are] an endless distraction”, and Time Magazine’s Richard Corliss said, “I thought I was watching a video game: pellucid pictures of indistinct creatures.” Advocates of HFR joined the fray and to an outsider it seemed as though the very fate of cinema was at stake.

Christie Digital, a projection company and HFR proponent, released a 2012 white paper that said the debate is akin to music lovers arguing over CDs and vinyl. “They embrace 24 fps just like audiophiles embrace the tone and warmth of 2” magnetic recording tape and old 33 RPM vinyl records,” the paper read.

The Globe and Mail’s film critic, Liam Lacey, discussed with me the historical relationship between technology and cinema and found a biased pattern: there are always those resistant to change. “You can probably still find people saying that film should have never transferred to colour,” Lacey said.

In Lacey’s review of The Hobbit, he described the movie’s visuals as, “somewhere between a soap opera, a sports bar football game and a direct-to-video kids program from a bygone era.” He titled his review, “The Hobbit: An epic adventure that’s hard on the eyes.”

Criticisms like Lacey’s piqued my interest in HFR; I was excited to see The Hobbit in 3D HFR. From production blogs and news articles, I gathered that the higher frame rate would greatly improve the look of high-speed action and reduce the jarring and fatiguing of 3D movies.

I saw the film in HFR IMAX 3D and initially agreed that it had a “cheap soap opera look.” But after a few minutes of acclimatizing, I completely forgot about the technology behind the movie, and the fact that I was wearing goofy 3D glasses. It wasn’t until the credits rolled that I realized I had no eye fatigue.

The best reason for going beyond 24 fps is to render 3D scenes with lots of movement more comfortable to watch. It also allows directors to shoot wide, sweeping landscapes, or pan across scenes without objects in the foreground acting as obstructions.

Stereoscopic or 3D movies work through slight differences in frames as seen by each eye. In most 3D setups, as the movie is played and frames are projected on the screen, polarized 3D glasses filter out frames. This way, certain frames are seen only by the left eye, and then the right eye, and so on. As 3D movies are shot with two cameras, there is a difference in the perspective viewing of that frame. The difference in perception gives the illusion of depth.

By doubling the number of frames, movement is better captured as it is spread across more frames. According to James Cameron in his 2011 presentation at CinemaCon, the problem is that movement in 3D film causes the edges of everything to flicker, known as strobing or chatter. Our brains pay more attention to edges in 3D because of the added depth, and this flickering is what gives some people eyestrain.

To understand the difference between 24/48/60 fps, you actually have to see it to believe it. It cannot yet be shown on YouTube, or on a DVD. You need content shot at different rates, and a projector capable of running at those speeds. Fortunately, I was able to tour Sheridan College’s Screen Industries Research and Training center to see the experiments they are doing with frame rates.

We were able to view James Cameron’s presentation on high-frame rate, which he gave at CinemaCon in 2011, as well as footage produced by SIRT. I was blown away at the difference in clarity and realism between the standard 24 fps and HFR.

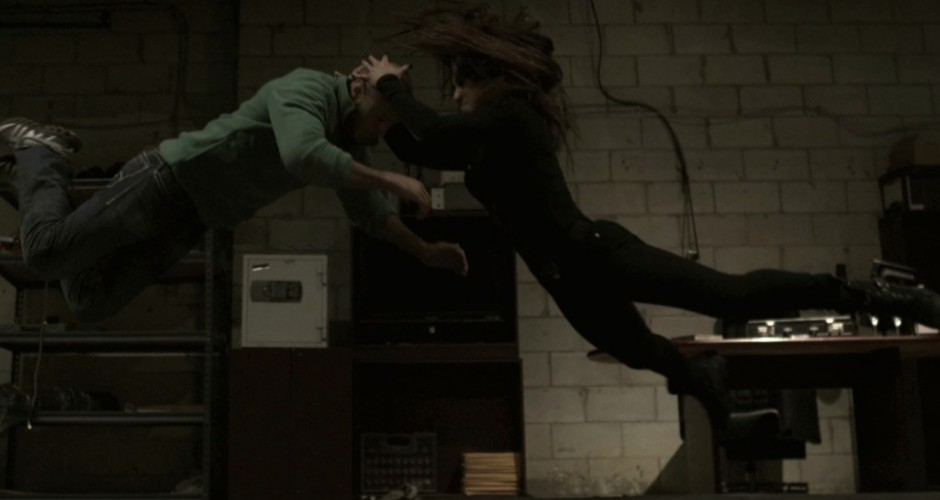

A jaw-dropping martial arts scene, for example, with swords flashing at blurring speeds, was almost devoid of any strobing, and the image was sharp and clean. At 60 fps, all evidence of strobing was removed, and the increased temporal resolution gave the appearance of watching a live play.

Bert Dunk, cinematographer and technology supervisor at SIRT, led me around the facility and explained the many aspects of HFR. While viewing sample footage he shot on location, he pointed out the flexibility of HFR.

“If the picture looks a little too sharp, they can soften it a bit more by going to a 270 [degree shutter angle],” said Dunk. In example footage, objects in the background were affected, but focused objects kept a level of detail and resolution not seen at 24 frames.

For cinematographers and directors like Dunk, making the switch to HFR shooting is as easy as pressing a button on a number of modern cameras. “Other than exposure, that’s the only difference,” said Dunk.

High Frame Rates, High Data Headaches

While those behind the camera may not need to change much to move beyond 24 frames, those behind the scenes in post-production and data storage face a much larger set of data.

I met with Peter Huang, a director and writer who had recently shot a music video at 120 fps on the RED Epic camera – the same camera used by Jackson in The Hobbit. Huang said that storytelling is what drives him, even in a four-minute music video.

While the music video wasn’t shown at 120 fps, Huang chose it to allow action sequences to match with music. He said the amount of data was incredible.

“At a certain point editing gets difficult, because you have to shove all that on a time line,” said Huang, adding that visual effects and slow motion requires a little more finessing. “But it’s really not that different. It’s just about storage.”

To learn more about HFR post-production, I spoke over the phone with Ian Bidgood, technical director at Park Road Post Production in New Zealand. Park Road handled the post-production for The Hobbit, and Bidgood was on the team that developed the process and algorithms for working with 48 fps footage.

What Park Road did was treat The Hobbit like a 24 fps movie for the offline, and 48 fps for the online. “In terms of the workflow for the offline, the editorial team and sound mixing were watching a 24 frame picture with time code at 24 frames,” explained Bidgood. “The 48 fps acquisition was just treated like a 24 frame film outside our online 48 fps editorial pipeline.”

Bidgood explained, “We had 48 frames that were recorded in the field, and we then graded the raw camera data for viewing at 48 frames back at Park Road Post. We then ‘disentangled it’, effectively only rendering every second frame for the editorial versions. So you now end up with a 24 frame version. This version was then used for the offline and sound mixing stages of the movie.”

Because the offline editing process is done at 24 fps, Bidgood says HFR post-production isn’t much different.

“It’s not much more work really, it’s just more data at the front and at our online stage … In terms of actual data-size for our storage, it’s no more than capturing a 2D movie in 4K: you’re doubling the data captured on the cameras, and because it’s a 3D film it’s already doubled from 2D.”

Looking forward, Bidgood sees a true 48 or 60 frame time code as the next step in development. In a statement he said, “As HFR becomes more widely accepted, hopefully along with it will be the introduction of 48 fps time code and monitors that support the 48 fps standard, from capture, through offline and into online, as one seamless pipeline, much like 24 fps is today.”

Keep the Cameras Rolling!

With worldwide box office earnings of over $1 billion, it’s safe to say The Hobbit and Park Road survived their plunge into HFR. Along with Cameron’s weight behind the technology, it’s fairly certain that more movies will be shown at speeds beyond 24 fps.

Yet the technology is still a fairly recent development. Bidgood noted several times during our conversation that Park Road had developed this entirely new system for editing film from scratch. Jackson and his crew were sent 24 fps rushes daily, as well as coming to Park Road to watch around three hours of footage in HFR.

Being the first blockbuster to delve into HFR, Jackson had the added burden of expectation on his shoulders. Lacey argued that successive films shot in HFR will be shown before a more receptive audience.

“For The Hobbit, people expected the Lord of the Rings experience and saw something else.” Lacey explained that the jutters and artifacts of 24 fps have become ”gauze” over film that we have become normalized to. “We like our fantasy seen through gauze,” he said.

As HFR becomes more common in the filmmaker’s toolbox, Dunk hopes to see movies shot and shown with dynamic frame rates – that is, the speed of camera and projector changing to suit the scene. For example, a scene of antiquity like Cameron’s sample footage of a medieval banquet, looks great and smooth at 48 fps, a big improvement over 24. Yet 60 fps became too sharp and clean, washing away the fuzz and dirt in the corners that would have existed in 14th century castles.

This ability is a long way away according to Bidgood, who has run experiments on dynamic frame rates. He says post-production costs would be “astronomically high” and keeping track of frames would be torturous.

“I can see it being just a nightmare, in terms of what stuff is running at 24 and what stuff is running at 48,” Bidgood said. “I’m not saying it’s impossible. But it would be a very difficult process.”

He adds that projector’s aren’t at a level where they can make a switch in frame rate without first going to black. In fact, projectors and post-production present the biggest challenge for HFR films. Cameras like the RED Epic are able to shoot 120 fps at 5K resolution. However, the majority of projectors are not capable of reaching those projection speeds.

Despite a number of technological puzzles to work out, what HFR allows filmmakers to do is remarkable. Yet film is an art form and as such, feelings about them are subjective. For some, juttering, strobing and artifacts are part of what makes a movie a movie.

Beauty is in the Camera Eye of the Beholder

Fears that HFR will trample what people are used to are hugely misplaced. Like 3D, make-up, CGI and green screens, HFR is just another tool filmmakers now have at their disposal.

“If you’re going to do Silver Linings Playbook, or A Royal Affair, or Anna Karenina, or anything of antiquity, by all means shoot in film and project it at 24,” said Huang. “But if you’re going to do it mostly in green screen, they should definitely, definitely, shoot it in 48 and in 3D.”

In conversation, Liam Lacey echoed Huang, despite finding The Hobbit’s appearance unappealing.

“It becomes a tool to identify which period you are shooting in,” said Lacey, providing the movie No by Pablo Larrain as an example of where the camera plays a huge role in setting the scene.

Larrain rebuilt Sony video cameras used in the 1980s when the film is set, giving the movie a “rough visual style” in Lacey’s words.

In his review of No, Lacey wrote, “Though initially off-putting, the rough visual style lets us immerse in the period’s visual tacky lo-def texture, while creating a continuum between the archival and freshly shot dramatic material.”

Really, there is no debate. No film czar is going to issue an edict relegating 24 fps to the dusty archives. And thanks to digital technology, classics can be stored indefinitely and easily projected.

“That’s the great thing about digital projection,” said Bidgood. “You can show your old archive films at 18 frames a second and you can show the new high-dynamic range, high frame rate films at 120 frames a second.”

Huang, while fascinated and enthralled with technology, appreciates and admires filmmakers who still tell stories through 35mm film.

In the end, Bidgood predicts that high frame rates will simply be another format that comes along, which some people will embrace and others won’t.